This is the Preface from my book, Maintainable Rails, available on Leanpub for half-price ($10USD) for the next month. Maintainable Rails demonstrates how to separate out the distinct responsibilities of a Rails application into smaller classes, leading to a more maintainable Rails application architecture.

When Rails came out, it was revolutionary. There was an order to everything.

Code for your business logic or code that talks to the database obviously belongs in the model.

Code that presents data in either HTML or JSON formats obviously belongs in the view.

Any special (or complex) view logic goes into helpers.

The thing that ties all of this together is obviously the controller.

It was (and still is) neat and orderly. Getting started with a Rails application is incredibly easy thanks to everything having a pre-assigned home.

The Rails Way™ enforces these conventions and suggests that this is the One True Way™ to organise a Rails application. This Rails Way™ suggests that, despite there being over a decade since Rails was crafted, that there still is no better way to organise an application than the MVC pattern that Rails originally came with.

While I agree that this way is still extremely simple and great for getting started within a Rails application, I do not agree that this is the best way to organise a Rails application in 2021 with long-term maintenance in mind.

As a friend of mine, Bo Jeanes put it neatly once:

Code is written for the first time only once.

Then there is anywhere between 0 and infinite days of having to change that code, understand that code, move that code, delete that code, document that code, etc. Rails makes it easy to write that code and to do some of those things early on, but often harder to do all the those things on an ongoing basis.

We benefit by being patient in that first period and maybe trading off some of that efficiency for a clarity and momentum for the life of the project.

A decade of Ruby development has produced some great alternatives to Rails’ MVC directory structure that are definitely worthwhile to consider.

In this book, I want to show an alternative viewpoint on how a Rails application should be organised in order to increase its maintainability.

These are the best pieces that I’ve found to work for me and others.

This research for how to construct a better Rails application comes out of 15 years worth of developing Rails applications.

To best understand why this alternative architecture is a better approach, we must first understand the ways in which Rails has failed.

Where Rails falls down

The Original Rails Way™ falls down in at least three major areas in my opinion. Three major areas that have to do with organization. Coincidentally (or not), these three areas are the major highlights of the way Rails suggests you organize applications: models, controllers, and views.

Let’s start with controllers.

Messy controllers

The controller’s actions talk to the model, asking the model to create, read, update or delete records in a database. And then this controller code might do more: send emails, enqueue background jobs, make requests to external services. There is no pre-determined, widely agreed-upon location for this logic; the controller is the de facto place. A controller action can often have request logic, business logic, external API calls and response logic all tied up in the one method, typically inside the action itself.

If this logic is not inside of the actions themselves, it is then likely found in private methods at the bottom of the controller. This leads to a common anti-pattern seen in Rails applications, one called the “iceberg controller”. What appears to be a small handful of clean actions is actually masking 100+ lines of private methods defined underneath. It is not immediately clear from scanning through these private methods which private method is used in which action. Or even if they are used at all!

Testing all these intertwining parts individually is hard work. To make sure that it all works together, you often have to write many feature and/or request tests to test the different ways that the controller action is called and utilized. The logic of the controller’s actions – those calls out to the model – get intimately acquainted with the logic for handling the request and response for that action. The lines between the incoming request, the business logic and the outgoing response become blurred. The controller’s responsibilities are complex because there is no other sensible place for this code to go.

The problems with Active Record Models

Controllers are bad, but models are worse. In order to remove complexity from controllers, it has been suggested to move that logic to the models instead – the “Fat model, skinny controller” paradigm.

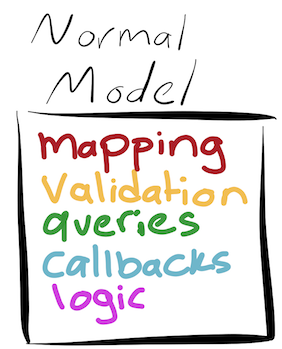

An Active Record model is responsible for at least the following things:

- Mapping database rows to Ruby objects

- Containing validation rules for those objects

- Managing the CRUD operations of those objects in the database (through

inheritance from

ActiveRecord::Base) - Providing a place to put code to run before those CRUD operations (callbacks)

- Containing complicated database queries

- Containing business logic for your application

- Defining associations between different models

If you were to colour each responsibility of your model, it might look something like this:

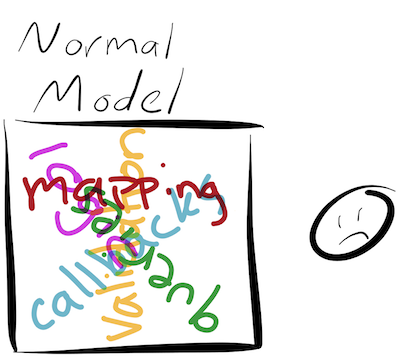

Or really, it might look like this:

In traditional Rails models, all of this gets muddled together in the model, making it very hard to disentangle code that talks to the database and code that is working with plain-Ruby objects.

For instance, if you saw this code:

class Project < ApplicationRecord

has_many :tickets

def contributors

tickets.map(&:user).uniq

end

end

You might know instinctively that this code is going to make a database call

to the tickets association for the Project instance, and then for each of

these Ticket objects it’s going to call its user method, which will load a

User record from the database.

Someone unfamiliar with Rails – like, say, a junior Ruby developer with very

little prior Rails exposure – might think this is bog-standard Ruby code

because that’s exactly what it looks like. That is what Rails is designed to look like. There’s something called

tickets, and you’re calling a map method on it, so they might guess that

tickets is an array. Then uniq further indicates that. But tickets is an

association method, and so a database query is made to load all the associated

tickets.

This kind of code is very, very easy to write in a Rails application because Rails applications are intentionally designed to be easy. “Look at all the things I’m not doing” and “provide sharp knives” and all that.

However, this code executes one query to load all the tickets, and then one

query per ticket to fetch its users. If we called this method in the console, then the query output might look like this:

Project Load (0.2ms) SELECT "projects".* FROM "projects" ORDER BY "projects"."id" ASC LIMIT ? [["LIMIT", 1]]

Ticket Load (0.1ms) SELECT "tickets".* FROM "tickets" WHERE "tickets"."project_id" = ? [["project_id", 1]]

User Load (0.1ms) SELECT "users".* FROM "users" WHERE "users"."id" = ? LIMIT ? [["id", 1], ["LIMIT", 1]]

User Load (0.1ms) SELECT "users".* FROM "users" WHERE "users"."id" = ? LIMIT ? [["id", 2], ["LIMIT", 1]]

User Load (0.1ms) SELECT "users".* FROM "users" WHERE "users"."id" = ? LIMIT ? [["id", 3], ["LIMIT", 1]]

User Load (0.1ms) SELECT "users".* FROM "users" WHERE "users"."id" = ? LIMIT ? [["id", 1], ["LIMIT", 1]]

User Load (0.1ms) SELECT "users".* FROM "users" WHERE "users"."id" = ? LIMIT ? [["id", 2], ["LIMIT", 1]]

User Load (0.1ms) SELECT "users".* FROM "users" WHERE "users"."id" = ? LIMIT ? [["id", 3], ["LIMIT", 1]]

This is a classic N+1 query, which Rails does not stop you from doing. It’s a

classic Active Record footgun / sharp knife. And this is all because Active Record makes it

much too easy to call out to the database. This code

for Project#contributors combines business logic intent (“find me all the

contributors to this project”) with database querying and it’s the major

problem with Active Record’s design.

What’s worse, is that you can make a database call wherever a model is used in a Rails application. If you use a model in a view, a view can make a database call. A view helper can. Anywhere! Rails’ attitude to this is one of “this is fine”, because they provide sharp knives and you’re supposed to trust the “omakase chefs” of the Rails core team. Constant vigilance can be exhausting, however.

Database queries are cheap to make because Active Record makes it so darn easy. When looking at the performance of a large, in-production Rails application, the number one thing I come across is slow database queries caused by methods just like this. Programmers writing innocent looking Ruby code that triggers not-so-innocent database activity is something that I’ve had to fix too many times within a Rails application.

Active Record makes it way too easy to make calls to the database. Once these database calls are ingrained in the model like this and things start depending on those calls being made, it becomes hard to refactor this code to reduce those queries. Even tracking down where queries are being made can be difficult due to the natural implicitness that some method calls produce database queries.

Thankfully, there are tools like AppSignal, Skylight and New Relic that point directly at the “smoking guns” of performance hits in a Rails application. Tools like these are invaluable. It would be nice to not need them so much in the first place, however.

The intention here with the contributors method is very innocent: get all the

users who have contributed to the project by iterating through all the tickets

and finding their users. If we had a Project instance (with thousands of

tickets), running that contributors method

would cause thousands of database queries to be executed against our database.

Of course, there is a way to make this all into two queries through Rails:

class Project < ApplicationRecord

def contributors

tickets.includes(:user).map(&:user).uniq

end

end

This will load all the tickets and their users in two separate queries, rather than one for tickets and then one for each ticket’s user, thanks to the power of eager loading. (Which you can read more about in the Active Record Querying guide.)

The queries look like this:

Ticket Load (0.4ms) SELECT "tickets".* FROM "tickets" WHERE "tickets"."project_id" = ? [["project_id", 1]]

User Load (0.4ms) SELECT "users".* FROM "users" WHERE "users"."id" IN (1, 5)

Active Record loads all the ticket objects that it needs to, and then it issues

a query to find all the users that match the user_id values from all the

tickets.

You can of course not load all the tickets at the start either, you could load only the 100 most recent tickets:

class Project < ApplicationRecord

def contributors

tickets.recent.includes(:user).map(&:user).uniq

end

end

class Ticket < ApplicationRecord

scope :recent, -> { limit(100) }

end

But I think this is still too much of a mish-mash of database querying and business logic. Where is the clear line between database querying and business logic in this method? It’s hard to tell. This is because Active Record allows us to do this sort of super-easy querying; intertwining Active Record’s tentacles with our business logic.

Views

Views in a typical Rails application are used to define logic for how to present data from models once this data has been fetched by controllers.

We’ve already discussed how Active Record allows you to execute additional queries in any context that a model is used. Typically additional queries like the tickets and contributors ones above will be executed in a view. There’s no clear barrier between models and views to prevent this from happening.

This sort of “leakage” makes it very hard for views to be used in complete isolation from a database. The moment a view uses a model is the moment that the view is now potentially tied to a database. For example: could you look at a view and quickly know how many, if any, database queries were being executed? Probably not.

To define any sort of Ruby logic for views, Rails recommends using view helpers. Perhaps we want to render a particular avatar for users:

module UsersHelper

def avatar

image_tag(user.avatar_url || "anonymous.png")

end

end

And then we were to use this in our view over at app/views/projects/show.html.erb:

<ul>

<% @project.tickets.each do |ticket| %>

<li><%= avatar(ticket.author) %></li>

<% end %>

</ul>

This code is defined in a helper file at app/helpers/users_helper.rb, but is used in a completely separate directory, under a completely different namespace. The distance between where the code is defined and where it is used is very far apart.

On top of all that, helpers are then shared across all views. So while the helper is defined in UsersHelper, it will be available for all views. If you define a helper in UsersHelper, then it is also available under views at app/views/tickets, or app/views/projects, too.

Because of this “wide sharing” of view helpers, we don’t know if changing it is going to have ramifications elsewhere in our application. If we change it for this one context, will it potentially break other areas? We cannot know without looking through our code diligently.

Presenters

A common way to approach solving this problem is through the presenter pattern. Presenters define classes that then “accentuate” models. They’re typically used to include presentational logic for models – things that would be “incorrect” to put in a model, but okay to put in a view.

By using a presenter, we have a clear indicator of where the presenter’s method is used: look for things like UserPresenter.new(user), and then that’ll be where it is used.

Here’s our avatar example, but this time in a presenter:

class UserPresenter

def avatar

image_tag(user.avatar_url || "anonymous.png")

end

end

To use this, we would then need to initialize a new instance of this presenter per user object:

<ul>

<% @project.tickets.each do |ticket| %>

<li><%= UserPresenter.new(ticket.author).avatar %></li>

<% end %>

</ul>

This then muddles together the Ruby and HTML code of our view. A way to solve this could be to move that preparation of the data into a helper:

module TicketsHelper

def author_avatar(author)

UserPresenter.new(author).avatar

end

end

Then in the view:

<ul>

<% @project.tickets.each do |ticket| %>

<li><%= author_avatar(ticket.author) %></li>

<% end %>

</ul>

We have now got the logic for rendering an avatar spread over three different points:

- The view

- The presenter

- The helper

This is not a very clear way to organize this code, and the more this pattern is used, the more confusing your application will get.

Views in a default Rails application leave us with no alternative other than to create a sticky combined mess of logic between our ERB files and helper files that are globally shared.

We can do better

It should be possible to render a view without relying on a model to be connected to a database. Being able to reach into the database from your views should be hard work. Your business logic should have everything it needs to work by the stage a view is being rendered. This will then make it easier to test the view in isolation from the other components of your application.

The source of these frustrations is the Active Record pattern and Rails’ strict adherence to it. A class containing only business logic and being passed some data should not need to know also about how that data is validated, any “callbacks” or how that data is persisted too. If a class knows about all of those things, it has too many responsibilities.

The Single Responsibility Principle says that a class or a module should only be responsible for one aspect of the application’s behaviour. It should only have one reason to change. An Active Record model of any meaningful size has many different reasons to change. Maybe there’s a validation that needs tweaking, or an association to be added. How about a scope, a class method or a plain old regular method, like the contributors one? All more reasons why changes could happen to the class.

An Active Record model flies in the face of the Single Responsibility Principle. I would go as far as to say this: Active Record leads you to writing code that is hard to maintain from the very first time you set foot in a Rails application. Just look at any sizable Rails application. The models are usually the messiest part and I really believe Active Record – both the design pattern and the gem that implements that pattern – is the cause.

Having a well-defined boundary between different pieces of code makes it easier to work with each piece. Active Record does not encourage this.

Validations and persistence should be their own separate responsibilities and separated into different classes, as should business logic. There should be specific, dedicated classes that only have the responsibility of talking to the database. Clear lines between the responsibilities here makes it so much easier to work with this code.

It becomes easier then to say: this class works with only validations and this other class talks to the database. There’s no muddying of the waters between the responsibilities of the classes. Each class has perhaps not one reason to change, but at least fewer reasons to change than Active Record classes.

It’s possible to build a Rails application with distinct classes for validations, persistence and logic that concerns itself with data from database records. It’s possible to build one that does not combine a heap of messy logic in a controller action, muddling it in with request and response handling.

Just because DHH & friends decided in 2006 that there was One True Way™ to build a Rails application – it does not mean that now in 2021, a full 15 years later, that we need to hew as close to that as possible.

We can explore other pathways. This is a book dedicated to charting that exploration, leading to a brighter future for your Rails application.

The way we’re going to improve upon the default Rails architecture is with two suites of gems: those from the dry-rb suite, and those from the rom-rb suite.

We’ll be using these gems to clearly demarcate the lines between responsibilities for our application.

We’ll have particular classes that will separate the code that validates user input from the code that talks to a database.

We’ll take apart the intermingling of request-response handling and business logic from within our controllers, and move that out to another set of distinct classes.

We’ll move code that would typically be in a view or a helper, into yet another type of distinct class: one called a view component.

And with this, we’ll move forward into that bright future that’ll lead to your Rails applications being maintainable.

_If you want to find out how to build maintainable Rails applications, read my book: Maintainable Rails, available on Leanpub for $10 for the next month.