When I’m writing my books, it’s more often than not that reviewers read and review these books on an application that I built myself called Twist. It looks like this:

In this post, I’d like to cover just one half of Twist: the backend half. There’s also a frontend half that’s just as interesting!

What’s most interesting about this backend application is that it is a Ruby application that is not a Rails application, and it is not a Sinatra application. While it borrows inspiration (and gems!) from the Hanami project, it is not a Hanami application. It’s a hybrid application, one that is built on top of some pretty great foundations from those Hanami gems, and also some gems from the dry-rb and rom-rb suites of gems. I’d like to spend this post covering a few key details here about Twist and its unique structure.

In this post I cover:

- The application container object

- Sub-system dependencies

- Entities, Repositories and Relations from rom-rb

- Receiving webhook requests from GitHub

- Background jobs

- Transactions

- The GraphQL API

To cover what Twist does in a nutshell: Twist receives webhook notifications from GitHub after new commits are pushed to a book’s GitHub repository. Twist then reads a book’s Markdown or AsciiDoc files and converts those formats into HTML and stores it in a database. Later on, that HTML is served out through a GraphQL endpoint in the form of books, chapters, and elements. Readers can then read the book and leave notes on the book as they go. I use these notes to improve the quality of the books I write.

If you want to get an idea of what working on this app is like, I’ve live streamed about 10 hours of active development on this project. The first episode is on Youtube here.

The application container

The application starts off in a similar way to a Rails application. There’s a config.ru file that goes off and loads config/boot.rb. That sets up Bundler and Dotenv, configuring the gems and environment necessary for running the application. After that, we come to the application container.

An application container is a concept from the dry-system gem. It’s a space to define the components of your application and how they’re loaded. Twist does this with the following code:

require 'dry/system/container'

require 'dry/auto_inject'

require 'dry/system/loader/autoloading'

require 'zeitwerk'

module Twist

class Container < Dry::System::Container

config.root = __dir__

config.component_dirs.loader = Dry::System::Loader::Autoloading

config.component_dirs.add_to_load_path = false

config.component_dirs.default_namespace = 'twist'

config.component_dirs.add "lib" do |dir|

dir.auto_register = true

dir.default_namespace = 'twist'

end

end

Import = Dry::AutoInject(Container)

end

loader = Zeitwerk::Loader.new

loader.inflector.inflect "graphql" => "GraphQL"

loader.inflector.inflect "cors" => "CORS"

loader.push_dir Twist::Container.config.root.join("lib").realpath

loader.setup

When this code defines a container for our application, it specifies component_dirs for that application. These are directories that contain code that is useful to our application. From here, twist specifies that anything in lib is something we want to register as components for this application. What’s great about this is that we’ve set this application up to be autoloaded, and so things are only ever loaded when we reference them. You get this feature with Rails, sure, but you also get it in dry-system too.

That autoloading is taken care of by the Zeitwerk gem. This gem will notice when you’re referencing a constant like Twist::Entities::Book, and if that constant hasn’t been loaded, it will attempt to load it from the lib/twist/entities/book.rb file. Throughout this application, all constants follow this naming pattern of where the path to the file matches the namespacing of the constant.

There are two special cases for Zeitwerk here where we want to inflect some words different to how Zeitwerk might try to. For GraphQL, Zeitwerk would look for a directory called graph_q_l by default. We can inform Zeitwerk should look for a directory called graphql by specifying that inflection rule near the bottom of this file.

When this container is finalized (with a call to finalize! in config/environment.rb), it will scan through the lib directory and register everything underneath it as keys within the application container. As a small example of the keys registered, here’s what happens when we ask the container for its keys:

Twist::Container.keys

=> ["oauth.client",

"database",

"authorization.book",

"entities.book",

"entities.book_note",

"entities.branch",

"entities.chapter",

"entities.comment",

"entities.commit",

"entities.element",

"entities.footnote",

"entities.image",

"entities.note",

"entities.note_count",

"entities.permission",

"entities.reader",

"entities.section",

"entities.user",

...

These keys and their naming will be relevant in a minute.

System Dependencies

dry-system has a concept of system dependencies – parts of your application that you can opt-in to booting along with finalizing your application container. In Twist, we have a large core dependency in system/boot/core.rb:

Twist::Container.boot(:core, namespace: true) do

use :persistence

init do

require 'babosa'

require 'redcarpet'

require 'nokogiri'

require 'pygments'

require 'sidekiq'

require 'dry/monads'

require 'dry/monads/do'

end

end

This file is responsible for requiring the different Ruby libraries that this application will need during its runtime.

The other file in this directory is called persistence.rb, and it defines the persistence system dependency:

Twist::Container.boot(:persistence) do

init do

require "rom-repository"

require "rom-changeset"

require "sequel"

end

start do

container = ROM.container(:sql, Sequel.connect(ENV['DATABASE_URL']), extensions: [:pg_json]) do |config|

config.auto_registration(File.expand_path("lib/twist"))

# config.gateways[:default].use_logger Logger.new(STDOUT)

end

register(:database, container)

end

end

It is possible to configure these dependencies in such a way that core could be booted separately from persistence, but I haven’t found a reason to uncouple these yet.

In persistence, there’s require statements for the persistence libraries, and then when the application starts up, a new container for ROM is created here. The container for the application that we saw earlier contains configuration for the application. The ROM container contains configuration for the database itself. This new container automatically registers ROM-specific things from lib/twist, which we’ll look at now.

Entities, Repositories and Relations

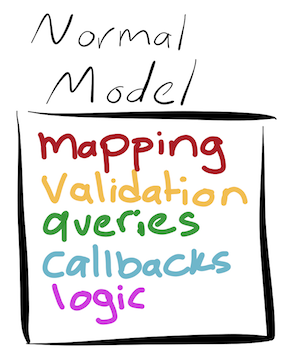

In order to interact with this database, Twist uses rom-rb. Where ActiveRecord would tie everything together in the one class:

These responsibilities are split out into several distinct classes within ROM-based applications.

- Entities: Ruby classes that use

ROM::Structto define attributes. - Relations: Classes that interact with a single database table and where complicated query logic lives.

- Repositories: Classes that serve as an adapter layer between relations and the application as a whole.

Entities

Here’s a quick example of an entity class:

module Twist

module Entities

class Book < ROM::Struct

attribute :id, Types::Integer

attribute :title, Types::String

attribute :permalink, Types::String

attribute :github_user, Types::String

attribute :github_repo, Types::String

def path

git = Git.new(

username: github_user,

repo: github_repo,

)

git.local_path

end

end

end

end

The attributes are defined right in the class, and so we don’t need to go skulking through db/schema.rb or the database itself or a console session to figure out what they are. We also get a type-safety of sorts here… if we attempt to assign a number to those string fields, this is what happens:

Dry::Struct::Error: [Twist::Entities::Book.new] 2 (Integer) has invalid type for :title violates constraints (type?(String, 2) failed)

Whereas a Rails app would just silently coerce the number into a string, ROM::Struct and its underlying Dry::Struct do not do that coercion and will warn you before you go ahead and do something you might later regret.

The path method here uses attributes from the entity to give us the path to a book on disk.

Note here that there is absolutely nothing to do with talking to a database in this class. Or validations. Or callbacks. The only code here is code that works with the attributes from the entity itself.

Repositories & Relations

Repositories are used to provide an interface layer between the relation classes that speak with the database and application-specific classes. Once data is returned from a repository, it is no longer possible to make database queries by calling additional methods on those returned objects.

In order to set this up to use the configuration from persistence.rb, Twist has a Repository class that imports the configuration:

module Twist

class Repository < ROM::Repository::Root

struct_namespace ::Twist::Entities

include Import[container: "database"]

end

end

The include statement here uses dry-auto_inject to find the database key’s configuration, and imports it here as container. All ROM repositories need to know the container that they’re operating in, so that they’re aware of which database to speak to.

A quick example of a repository would be the BranchRepo:

module Twist

module Repositories

class BranchRepo < Twist::Repository[:branches]

commands :create, use: :timestamps, plugins_options: { timestamps: { timestamps: %i(created_at updated_at) } }

def by_book(book_id)

branches.where(book_id: book_id).to_a

end

def by_id(id)

branches.by_pk(id).one

end

...

ROM Repositories do not immediately offer us things such as create or update – we have to opt into them. That’s what’s happening here with the first line that specifies commands here.

The by_book and by_id methods here use another method called branches. This method is an instance of the Twist::Relations::Branches class and we can then call methods on that to query the database.

If we have particularly complicated query logic, we extract that logic out to relations. An example of this is the code from NoteRepo:

# rubocop:disable Metrics/AbcSize

def count(element_ids, state)

counts = notes.counts_for_elements(element_ids, state)

missing = element_ids.select { |id| counts.none? { |c| c.element_id == id } }

counts += missing.map { |m| Entities::NoteCount.new(element_id: m, count: 0) }

counts.map { |nc| [nc.element_id, nc.count] }.to_h

end

# rubocop:enable Metrics/AbcSize

The counts_for_elements method used here is defined within Twist::Relations::Notes:

module Twist

module Relations

class Notes < ROM::Relation[:sql]

schema(:notes, infer: true)

def counts_for_elements(element_ids, state)

where(element_id: element_ids)

.where(state: state)

.select { [element_id, function(:count, :id).as(:count)] }

.group(:element_id)

.order(nil)

.to_a

end

end

end

end

What’s happening here is that we’ve got two spots of complicated logic: one where we need to query the database for the note counts for a range of elements, and another where we need to do some massaging of that data into Entities::NoteCount objects. By having the code split up into repositories and relations here, we’re able to have a clear “home” for the code that talks to the database (that’s the relation) and then code that massages that data belongs in the repository. In a typical Rails application, you would throw everything together into one super method in the model.

This count method on the NoteRepo will return a confusing looking hash:

Twist::Container["repositories.note_repo"].count([16], "open")

=> {16=>1}

This hash is not fit for human consumption, but is later sent through an API and then made fit for human consumption. The key is the element ID, and the values are the number of notes for that element.

How about another example, that is “fit for human consumption”?

Twist::Container["repositories.branch_repo"].by_book(1)

=> [

#<Twist::Entities::Branch

id=1

name="master"

default=true

book_id=1

created_at=2021-08-11 14:59:48.203662 +1000

updated_at=2021-08-11 14:59:48.203662 +1000

>

]

When we call the by_book method on the BranchRepo, that class reaches out to the branches relation and performs a where query, finding all branches for a particular book. When the data comes back from the database, it’s mapped into Twist::Entities::Branch objects. These entities are then very bare-bones:

[10] pry(main)> ls Twist::Container["repositories.branch_repo"].by_book(1).first

#<Dry::Core::Equalizer:0x00007fba268d3140>#methods: freeze hash

Dry::Core::Equalizer::Methods#methods: == eql?

Dry::Struct#methods: [] __attributes__ __new__ attributes deconstruct_keys inspect new to_h to_hash

ROM::Struct#methods: fetch

Twist::Entities::Branch#methods: default id name

Twist::Entities::Branch#methods: book_id created_at updated_at

instance variables: @attributes

Not counting methods from Object.methods, there are only 13 methods available on this object. A typical Active Record model will have around 300 different methods, but that varies based on the number of attributes it has too, as it adds in meta-programmed methods like title_will_change? from ActiveModel::Dirty and friends. I think 300 methods is a lot.

Receiving webhook requests

Twist’s primary purpose is to serve as a two-endpoint Rack app. The first endpoint – /books/:permalink/receive – is used by GitHub’s webhooks system. The second is /graphql.

GitHub notifies Twist through the “receive” endpoint whenever a book’s repository is updated. The route for this request is defined in the web part of Twist.

It’s here that it’s probably best to mention that Twist’s backend is split into two distinct parts. There’s the regular Ruby stuff, and the web stuff.

The “regular Ruby stuff” includes things like Twist::Entities::Book, a class that is used to represent data about a book within the application. The “regular” side of the application also includes the relations and repositories that we saw earlier. Let’s not also forget to mention that the “regular” directory also contains transactions, which are classes that perform one, and only one, transaction within the application. Things like creating a new note, or inviting a new reader to a book.

Over on the “web” side of the application (lib/twist/web), you’ll find the stuff you know and love from Rails: your router, your controllers, the actions.

The router is defined as a Hanami router:

module Twist

module Web

Router = Hanami::Router.new do

if ENV['APP_ENV'] == "development"

require 'sidekiq/web'

mount Sidekiq::Web, at: '/sidekiq'

end

post '/graphql', to: Controllers::GraphQL::Run.new

options '/graphql', to: Controllers::GraphQL::Run.new

post '/books/:permalink/receive', to: Controllers::Books::Receive.new

get '/oauth/authorize', to: Controllers::Oauth::Authorize.new

get '/oauth/callback', to: Controllers::Oauth::Callback.new

end

end

end

As you can see from this code, routes do not route to one giant controller class with several actions inside it. Instead, each action is its own class. This concept makes it much easier to jump to the code for one particular action, without being confused about what code is relevant to which action inside a controller – like what might happen to you in a standard Rails application. An example of this is that the authorize and callback actions associated with the OAuth parts of this application are their own separate classes here.

We’re straying a little off track there, so let’s get back on track: the /books/:permalink/receive route. That route goes to the Controllers::Books::Receive action, which is defined in lib/twist/web/controllers/books/receive.rb. Note here that the path here matches the constant – this is something that Zeitwerk enforces so that it can automatically load our constant when we need it.

This controller starts out in an interesting way:

module Twist

module Web

module Controllers

module Books

class Receive < Hanami::Action

include Twist::Import[

find_book: "transactions.books.find",

find_or_create_branch: "transactions.branches.find_or_create"

]

An include statement at the top of a controller that isn’t doing something like include ApplicationHelper? This certainly seems like some sort of black magic – at least that’s what I thought when I originally saw it.

What this is doing is including two helpful transactions from within our application’s container. This code will find the classes registered under the keys transactions.books.find and transactions.branches.find_or_create and it will load those classes at this point. Not only are these classes loaded, but new instances of these classes are initialized at this point too. And not only that, but these instances are then made available through the methods find_book and find_or_create_branch within this controller.

This is made possible by another dry-rb gem called dry-auto_inject.

Later on this controller, we can refer to these instances and call the call method on these transactions by writing code such as:

book = find_book.(permalink: req.params[:permalink])

And:

branch = find_or_create_branch.(book_id: book.id, ref: payload["ref"])

It’s worth noting that similar includes / imports can be found in those transaction classes too:

module Twist

module Transactions

module Books

class Find

include Twist::Import["repositories.book_repo"]

def call(permalink:)

book_repo.find_by_permalink(permalink)

end

end

end

end

end

The benefit here of using dry-auto_inject is that we can quickly include dependencies from across our application into other classes. dry-auto_inject works by re-defining the initialize method wherever it is used to something similar to this:

def initialize(find_book: Twist::Container['transactions.books.find'], find_or_create_branch: Twist::Container['transactions.branches.find_or_create'])

@find_book = find_book

@find_or_create_branch = find_or_create_branch

end

This means that we could change away from the default values here to something else entirely. A good example of where we might like to do that is within tests. You’ll see an example of this over in backend/spec/twist_web/controllers/books/receive_spec.rb.

describe Twist::Web::Controllers::Books::Receive do

let(:find_or_create_branch) do

->(book_id:, ref:) { branch }

end

subject do

described_class.new(

find_or_create_branch: find_or_create_branch,

...

)

end

The test for this action immediately stubs out find_or_create_branch and will return a branch object for whatever’s passed in. Later on in the test, that variable is defined as:

let(:branch) { double(Twist::Entities::Branch, name: "master") }

This means that we don’t need to set up messy test data within factories – we can stub out our transactions to return simple doubles here instead. This means that the tests for this controller action are remarkably quick. In fact, by following this pattern throughout the whole application all of the application’s tests are remarkably quick! The slowest ones are ones that need to interact with a filesystem.

There are about 150 tests for this application so far and they take about 12 seconds to run.

Speaking of: when Twist receives a book, it enqueues that book for processing through one of its processor classes, either Twist::Processors::Markdown::BookWorker or its AsciiDoc equivalent. Let’s look at what happens then.

Background jobs

Receiving a webhook from GitHub takes a very short time. I really wish I could say the same for processing a book! However, there are some complexities here.

First, Twist needs to pull the latest changes from GitHub. By this point, Twist has only been notified that changes have happened – it doesn’t exactly know what’s changed. Twist runs a background job with Sidekiq that does a git pull on the book’s Git repository. From there, Twist will read each of the book’s chapters in a separate background job and convert the chapters into HTML. From there, it processes each individual HTML element using classes such as Twist::Processors::Markdown::ElementProcessor. I won’t go so much into this code, as it’s more Twist-specific than applicable to other codebases.

The complexities here involve downloading the code from GitHub, and uploading the images to S3. Each image is processed as another async job separate from the book and chapter async workers. The main issue here is that, for a few brief seconds, the words of a chapter can be available on Twist, but sometimes the images will not have finished processing.

In the end, what we end up with in the database is a new commit from GitHub tied to the book, and under that commit are the relevant chapters, and under those chapters their elements, such as section headings, paragraphs and images.

Transactions

Transactions are classes within Twist that perform a single operation / action / transaction. Let’s look at how a JWT is decoded within Twist.

module Twist

module Transactions

module Users

class FindCurrentUser < Transaction

include Twist::Import["repositories.user_repo"]

def call(token)

return Failure("no token specified") if !token || token.length == 0

token = token.split.last

return Failure("no token specified") unless token

payload, _headers = JWT.decode token, ENV.fetch('AUTH_TOKEN_SECRET'), true, algorithm: 'HS256'

user = user_repo.find_by_email(payload["email"])

user ? Success(user) : Failure("no user found")

end

end

end

end

end

This class inherits from Twist::Transaction, and that class defines some common transaction things:

module Twist

class Transaction

def self.inherited(base)

base.include Dry::Monads[:result]

base.include Dry::Monads::Do.for(:call)

end

def permission_denied!

Failure("You must be an author to do that.")

end

end

end

The dry-monads gem here provides Result objects, which can be used to short-circuit the execution of transactions to bail out early if things are going wrong. In the call method of this transaction, we have failure cases where the token might be missing or too short, or if a user couldn’t be found that matched a provided token. We have a single Success() case if the user could be found here.

We’re able to assert on the outcome of this transaction by calling .success? or .failure? on it, as indicated by this class’s tests:

require "spec_helper"

module Twist

describe Transactions::Users::FindCurrentUser do

include Twist::Import[

"transactions.users.generate_jwt",

create_user: "transactions.users.create"

]

let(:user) do

create_user.(

email: "me@ryanbigg.com",

name: "Ryan Bigg",

password: "password",

github_login: "radar",

).success

end

let(:token) { generate_jwt.(email: user.email).success }

it "finds a user by a given JWT token" do

result = subject.(token)

expect(result).to be_success

expect(result.success).to eq(user)

end

it "finds no user with a nil token" do

result = subject.(nil)

expect(result).to be_failure

end

it "finds no user with a blank token" do

result = subject.("")

expect(result).to be_failure

end

end

end

The benefit of using Success and Failure objects from dry-monads is that we can easily check for the success or failure of any transaction within the application.

GraphQL

As I mentioned at the start of this post, Twist is two distinct applications – a frontend application written in TypeScript + React and a backend application written in Ruby. To get the two to communicate nicely with each other I use GraphQL. GraphQL is great here as we can easily define the types of objects on the Ruby side of things, and have those same types available in the frontend.

Requests come in through the router and head to the Twist::Web::Controllers::GraphQL::Run action. This action sets up a Twist::Web::GraphQL::Runner to run the queries themselves. This second class exists so that I can test GraphQL queries separate from a request / response stack if I need to.

Ultimately, this code path leads us to twist/web/graphql/query_type.rb, which defines fields and how they’re resolved for queries:

module Twist

module Web

module GraphQL

class QueryType < ::GraphQL::Schema::Object

graphql_name "Query"

description "The query root of this schema"

field :books, [Types::Book], null: false, resolver: Resolvers::Books

The types are defined like this:

module Twist

module Web

module GraphQL

module Types

class Book < ::GraphQL::Schema::Object

graphql_name "Book"

description "A book"

field :id, ID, null: false

field :title, String, null: false

field :blurb, String, null: false

field :permalink, String, null: false

While the resolver above is defined like this:

module Twist

module Web

module GraphQL

module Resolvers

class Books < Resolver

def resolve

books = context[:book_repo].all

books.select do |book|

authorization = Authorization::Book.new(

book: book,

user: current_user,

permission_repo: context[:permission_repo],

)

authorization.success?

end

end

end

end

end

end

end

It’s tempting to me to move most of this logic of the resolver out to a distinct Twist::Transaction class, but this code is only used within the resolver here. I think I would move it out to that transaction if I wanted to share it across the different parts of the application.

It’s important to note here that because we’re in GraphQL-land, we do as the GraphQL’ers do and read things like the book_repo and permission_repo from the context, rather than include-importing them. This then groups together all different context-related things into one variable, rather than having to chop and change between context and imported values.

When writing these GraphQL queries, I’ll typically start building out something in the frontend first. Once I’m happy with the structure, I’ll map that to a GraphQL query and then write a spec around it before writing the Ruby code to fulfill the query. Here’s the related spec for this books query:

require "requests_helper"

module Twist

describe "Books", type: :request do

let(:create_book) { Twist::Container["transactions.books.create"] }

let!(:create_user) { Twist::Container["transactions.users.create"] }

let!(:grant_permission) { Twist::Container["transactions.users.grant_permission"] }

let!(:book) { create_book.(title: "Rails 4 in Action", default_branch: "master").success }

let!(:user) do

create_user.(

email: "me@ryanbigg.com",

password: "password",

name: "Ryan Bigg",

).success

end

before do

grant_permission.(user: user, book: book)

end

it "gets a list of books" do

query = <<~QUERY

{

books {

id

permalink

title

defaultBranch {

name

}

}

}

QUERY

query!(query: query, user: user)

expect(json_body).to eq({

"data" => {

"books" => [

{

"id" => book.id.to_s,

"permalink" => book.permalink,

"title" => book.title,

"defaultBranch" => {

"name" => "master"

}

}

]

}

})

end

end

end

It’s important to note here that the request specs in this application are the only place where we’re interacting with a database. I feel like this is necessary to ensure that the queries are working completely from end-to-end. If I was to stub something here, there’s no guarantee that the shape of what I’m stubbing matches exactly the shape of what would be returned by a database query.

So instead of hoping / praying that my stubbing is correct, I instead create real objects for books, users and permissions in this test. When the GraphQL query runs, it gets served by the real action and that queries a real (test) database and I can then assert that the data being returned here is what I intended it to be.

What’s really great here is that if I change the query on the frontend, I can just copy and paste it right into this spec without having to map it to something Ruby-ish. The same principle applies if I’m going the other way too. I really like that about GraphQL.

The final thing I’ll mention about GraphQL is that over in the Rakefile for this application I have a task setup to dump the GraphQL schema out:

require "graphql/rake_task"

GraphQL::RakeTask.new(

schema_name: "Twist::Web::GraphQL::Schema",

directory: "../graphql",

dependencies: [:environment]

)

This dumps out a graphql/schema.graphql file as well as a graphql/schema.json file. These files are then read by some frontend tasks to automatically generate TypeScript types using the graphql-codegen library. This is then used to ensure that the types that I’ve defined in the GraphQL schema are exactly matching to the ones used over in the frontend. Without this, I reckon ensuring consistency between the backend and frontend applications would’ve been a major headache.

Summary

So there you have it, a grand tour of the Twist application with my favourite highlights. I really enjoy working within this application, moreso than any Rails application that I’ve ever touched. And sure, that might be because I was the one who wrote this app and I’m the only one who maintains it.

But, really, it’s more than that.

The clean layers of separation between things like the entities, repositories and relations make it really easy to reason about where code should go.

Transactions provide me a clear way of separating out application operations away from code that might’ve otherwise gone inside actions. I can then share this code between different parts of my application easily without worrying about having to untie it from a controller’s grasp.

And the GraphQL API provides a clear, distinct layer between my backend and frontend application parts, while still allowing an enforcement of the datatypes across the barrier.

It’s really a joy to work in.

If you like what you see in this post, you might also like to read my book Maintainable Rails which is just $5 at the moment. This book demonstrates how to bring the concepts shown in this post into a brand new Rails application, ultimately leading to an application that is easier to maintain in the long-term.